December 21, 1969 7:51am

Crew: Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, William Anders

Duration: 6 days, 3 hours, 42 seconds

The flight of Apollo 8 in December of 1969 marked the beginning of the end of the Space Race.

Apollo 8 had originally been planned as a “D” mission, a test of the lunar module in low earth orbit. The initial crew was James McDivitt, David Scott, and Rusty Schweickart. Frank Borman and his crew would then fly the “E” mission, another test of the Lunar Module in a higher orbit. Only then would Apollo reach for the Moon, the “F” mission, testing the Lunar Module in orbit around the Moon. If all went well, the next step would be actually landing on the Moon in the “G” mission.

But that schedule started falling apart when NASA inspectors examined LM-3, the Lunar Module selected for Apollo 8. They discovered more than a hundred defects, and NASA engineers realized it would take months to fix them all. It would be able to fly in 1968. With Kennedy’s deadline fast approaching, the delay would set the entire program back by months.

In addition, there was evidence that the Soviets were preparing to send a cosmonaut aboard a Zond spacecraft to circle the Moon and return to Earth.

George Low, the Manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, had an idea. The plan was simple. Instead of waiting for the Lunar Module, Apollo 8 would launch in December and either fly around or orbit the Moon. In August of 1968, he began sharing his it with other NASA leaders. They agreed it could be done and were able to convince NASA Administrator Jim Webb to authorize the mission. There were conditions. The flight of Apollo 7 would have to be a success, and NASA would have to keep their intentions quiet until everything came together.

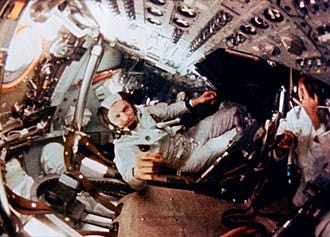

But preparations began immediately. Slayton offered the mission to McDivitt. He turned it down. He and his crew had been training rigorously for their mission to test the Lunar Module in low earth orbit, and he wanted to fly that mission. Frank Borman took the job. Jim Lovell replaced Michael Collins, who had to undergo back surgery in July, as the Command Module Pilot and William Anders was the Lunar Module Pilot. Anders was disappointed because he’d been training to fly the LM and Apollo 8 would only carry a boilerplate version. The crew went to work in the simulators on September 9th. By November, they were training ten hours a day, seven days a week.

Von Braun and his team had been working on the problems experienced by the unmanned Apollo 6 test in April. They installed a system that used helium gas to counteract the pogo oscillations. And they traced the engine shutdowns to leaky fuel lines, which they corrected. AS-503, as it was called, was declared ready to fly.

The assembled stack rolled out to Launch Complex 39A on October 9th, two days before the launch of Apollo 7 from Launch Complex 34. Testing continued until the day before the launch.

At 2:30 am on December 21st, Borman, Lovell, and Anders were awakened for breakfast. Afterward, they were wired up for the biomedical sensors and suited up. The transfer van drove them the three miles to their awaiting spacecraft. A huge crowd of invited guests, spectators, and journalists gathered in the pre-dawn hours to watch the launch.

At 7:51 am, the launch sequence began. The mighty F-1 engines of the first stage ignited and slowly built up thrust. Seconds later, the clamps that held the rocket down released. The support umbilical’s detached and the mobile launcher tower’s support arms swung away as the rocket began to move. For the first time, astronauts were riding the Saturn V. Borman and Lovell later said the launch was similar to what they had experienced on the Gemini missions that used the Titan II booster. Anders, who was on his first flight, said it was like riding “an old freight train going down a bad track.”

Step by step, Apollo 8 climbed through the atmosphere. The S-IC first stage did its job without a hitch, as did the S-II second stage. The third stage S-IVB kicked the stack into orbit right on schedule.

Now came the test. The S-IVB engine had to relight for translunar injection. It had failed on the last unmanned test. After checking and rechecking, Mission Control was ready. Two hours and twenty-seven minutes after launch, CapCom Michael Collins informed the crew: “Apollo 8, you are go for TLI.” The S-IVB engine fired up again, accelerating the stack from 17,000 mph to an astonishing 24,158 mph. The translunar injection was complete. Apollo 8 was headed to the Moon.

The CSM separated from the S-IVB and the boilerplate LM. The crew maneuvered around the third stage booster, taking photographs. They maneuvered away, and Mission Control sent the command for the booster to vent its remaining fuel. It entered solar orbit where it remains to this day.

Eleven hours after liftoff, the crew had to perform a mid-course correction. The fired the Service Module engine for 2.4 seconds, but it underperformed, and they had to use the Reaction Control System thrusters to make up the difference. The result was a perfect trajectory, and no further corrections would be needed.

At this point, Frank Borman took the first sleep shift. After tossing and turning a bit, he got permission to take a sleeping pill. After finally falling asleep, he awoke, feeling sick. He vomited twice and suffered a bout of diarrhea. The crew cleaned up the resulting mess. Borman wanted to keep the matter quiet, and the crew compromised, recording a message on the Data Storage Equipment, sent it via high-speed transmission, and suggested Mission Control review it for “an evaluation of the voice comments.”

After reviewing the situation with the NASA flight surgeons, they decided it was either a reaction to the sleeping pill or the 24-hour flu. As it turned out, he was suffering from space adaptation syndrome, which would be a recurrent problem on later missions.

As the journey to the Moon continued, the crew carried out various tasks, including two television broadcasts, sending back the first live television images of the Earth. Although they were fast approaching the Moon, they were unable to see it because of the direction the spacecraft was required to face and because three of the five windows had fogged up. “We took it on faith the Moon would be there,” Lovell said later.

Fifty-five hours into the mission, the CSM passed the point where the Moon’s gravitational influence became stronger than the pull of gravity from the Earth. Another correction burn adjusted their trajectory so that they would now fly just 71.7 miles over the Moon’s surface. The next maneuver would be the Lunar Orbit Insertion, which would have to be performed out of radio contact with Earth on the far side of the Moon. Mission Control gave them the go, and Lovell replied, “We’ll see you on the other side.”

The crew got their first close up view of the moon just two minutes before the LOI burn. They had little time to appreciate it. Sixty-nine hours after the mission began, the Service Module Engine fired up and burned for four minutes and seven seconds. They were now in an elliptical orbit, 193.3 miles at its highest point and 69.5 miles at the lowest.

Apollo 8 orbited the moon ten times in the next twenty hours. Jim Lovell described what he saw. “The Moon is essentially grey, no color,” he told Mission Control. “We can see quite a bit of detail.”

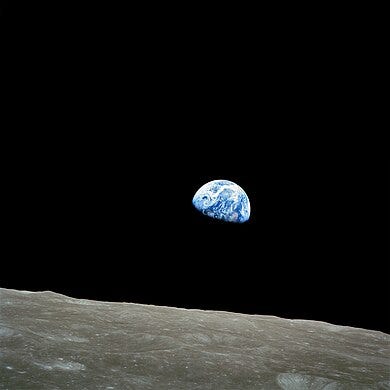

Bill Anders, who originally been training to fly the Lunar Module, was given the task of taking photographs of potential landing sites for future missions. On their fourth pass over the near side, they spotted the Earth rising over the horizon of the Moon. Anders captured the magnificent sight with a black and white photograph, and then the famous color photograph that became known as Earthrise.

Borman slept fitfully for two orbits, and when he awoke, he ordered his exhausted crew to get some sleep as well. He wanted them to be well-rested when it came time to fire the engine again for the trans-Earth injection and the trip home.

Coming out from behind the far side on their ninth orbit, the crew began its second television broadcast. It was Christmas Eve, and the crew had planned something special. They took turns reading from the Book of Genesis.

Anders:

“We are now approaching lunar sunrise, and for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you. In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.”

Lovell:

“And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day.”

Borman:

“And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so. And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called the Seas: and God saw that it was good. And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas – and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

The live broadcast was viewed around the world, by what was the largest television audience to that point in history. Its impact was powerful. “The message from the crew really got to me,” Robert Bay, now a Grumman contractor, recalled. “I kept getting something in my eyes that kept them moist for a while.”

There was one final and critical task. On their final orbit, out of radio contact on the far side, the crew fired up the Service Module Engine again. Mission Control and the world waited almost breathlessly to learn the result. As contact was reestablished, Jim Lovell told those listening, “Please be informed, there is a Santa Claus.” The burn was perfect. Apollo 8 was now just three days from home.

It was Christmas day. The crew made another television broadcast. Then they discovered the gifts Deke Slayton had provided. There was a real turkey dinner, complete with stuffing, hidden in the food locker. And there were three miniature bottles of brandy. The crew relished the turkey, but the brandy bottles remained unopened for years.

The remainder of the cruise home was uneventful. Re-entry began on December 27th, controlled by the flight computer, and the Command Module splashed down in the Pacific southwest of Hawaii. The parachutes dragged the spacecraft over and left it bobbing upside down in choppy water, making Borman sick again. Six minutes after splashdown, the floatation system righted the capsule. Thirty-seven minutes later, the rescue helicopter arrived, and the crew was aboard the U.S.S. Yorktown forty-five minutes later.

1968 had been a horrible year. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy had both been assassinated. There had been violent protests in the streets of the United States and Europe. The Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies had invaded Czechoslovakia to shut down the political uprising there. The Vietnam War was intensifying in the wake of the Tet Offensive.

But Apollo 8 had ended the year on a much more positive note. Time Magazine made the crew its ‘Men of the Year.’ The Earthrise photograph was the first of Life Magazine’s 100 Photographs That Changed the World. It was also credited as one of the inspirations for the first Earth Day celebration in 1970. The television broadcasts were awarded an Emmy.

But perhaps nothing sums up the impact of Apollo 8 more than a telegraph Borman received from a stranger. “Thank you Apollo 8,” it read. “You saved 1968.”

It had been a risky decision, but NASA had now cleared one of the last hurdles before it could send a manned mission to the Moon. There was only a year left to meet Kennedy’s challenge. The focus would now turn to the last hurdle, the Lunar Module.