July 16, 1969

Crew: Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Edwin Aldrin

Duration: 8 days, 3 hours, 18 minutes, 35 seconds

It had been eight years, and now NASA was ready to fulfill John F. Kennedy’s challenge.

On the morning of July 16th, there were an estimated one million people crowded along the streets and beaches with views of the launch pad (I was one of them). 20,000 guests were given seats in the NASA viewing stands. 3,500 of them were journalists from around the world. The launch would be televised and seen live by up to a billion people.

The launch was spectacular. The crew reported a smooth ride, without any of the pogo oscillations previous flights had been through.

After trans-lunar injection, they jettisoned the third stage and retrieved the Eagle.

They required only one mid-course correction on the journey to the moon.

On July 19th, Apollo 11 crossed over into the lunar sphere of influence. The world was watching as the hatches on Columbia and Eagle were opened, and Aldrin floated into the Lunar Module for the first time.

Apollo 11 slipped behind the dark side of the Moon and fired up the SPS for the lunar orbit insertion. During their first two orbits, they could see their landing site growing brighter.

There was a nine-hour rest period, but none of the crew slept well.

After a quick breakfast, Armstrong and Aldrin boarded the Eagle. Collins went through the lengthy process of closing up the hatches and running through the details of his checklist. On their thirteenth orbit, the two spacecraft separated. “The Eagle has wings,” Armstrong reported.

The crew aboard Eagle meticulously checked out their systems. They fired up the landing radar. Then the real drama began. Armstrong slowly fired up the descent engine, slowing Eagle and dropping to down toward the surface. The process would take twelve minutes, but to everyone watching, it seemed to take forever.

On the way down, a series of alarms jangled nerves. The tension was intense in Mission Control, as the team of controllers tried to confirm everything was okay.

The Eagle rotated, and with just three minutes left, Armstrong and Aldrin got their first good look at the path ahead of them. They were less than two thousand feet above the surface. Armstrong recognized the landing site immediately and saw it was crowded with boulders. He gave the engine a goose to fly past the boulders and spotted smoother ground ahead.

The Descent Module’s fuel supply was quickly running out, and Mission Control began to sweat. Aldrin called out the altitude and speed. At a hundred feet, the Descent Engine started kicking up lunar dust, obscuring the view from the windows. At thirty feet, the Eagle began drifting slightly backward and to the left. Armstrong corrected the backward movement. He was concentrating so hard, he didn’t hear Aldrin call out “contact light,” the point at which the sensors hanging sixty-seven inches below the Eagle’s landing pads touched the surface.

The Eagle settled to the surface, and Armstrong cut the engine. The instruments in Mission Control indicated a landing.

“We copy you down, Eagle,” radioed CapCom Charlie Duke.

“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

238,900 miles away, there was a moment of joyous celebration in Mission Control, and from the people watching around the world. Walter Cronkite was sitting next to Wally Schirra for the live coverage. Schirra could be seen wiping a tear from his eye while Cronkite breathed a sigh of relief. “Man on the moon,” he said, removing his classes. “Whew. Boy!”

“Roger, Tranquility, we copy you on the ground,” Duke responded over the cheers. “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot!”

“And then the backroom literally erupted,” Flight Director Gene Kranz recalled. “The people were pounding on the floors, cheering and applauding us. And then my control room started to pick up the same buzz, and I said okay all you guys, settle down.” Kranz would go on to say he wished he and his team could have enjoyed the moment more. But there was no time for celebration in the moment. Mission Control had to determine if it was safe to stay on the surface. And before anything else could happen, Armstrong and Aldrin would have to prepare the Eagle for an emergency liftoff.

With that checklist completed, the crew was supposed to have a five hour rest period before stepping down to the surface. But they knew they’d never actually rest. Mission Control agreed to begin the EVA early.

It took almost twice as long to prepare as it had during training, mostly because they were especially cautious. Suited up, they depressurized the Eagle, and six hours and twenty-one minutes after landing they pulled open the hatch.

Armstrong, with his bulky backpack, had to wiggle carefully through with Aldrin guiding him. Out on the porch, he surveyed the landing site and pulled the latch that released the experiments compartment and the television camera that would monitor his climb down to the surface.

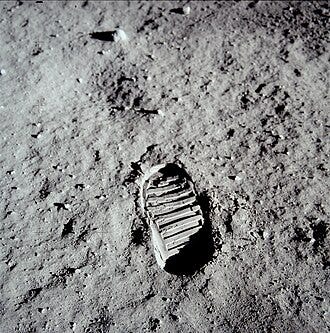

Then he descended the nine-rung ladder and stepped on to the land pad. He hopped back up to the ladder to make sure he’d be able to reach it easily, before dropping back down to the landing pad. After making some observations about the surface, he radioed Mission Control. “I’m about to step off the LM now.” With hundreds of millions of people watching back home, he took the step.

“That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind,” he reported. He had intended to say it was a “small step for a man,” and may have, but the transmission was garbled.

Now Armstrong took a few minutes to get a feel for moving around on the surface. He reported that it was easier than it had been in the simulations, “it’s absolutely no trouble to walk around.” To make sure they would have something to show for all the trouble if something went wrong, he collected a sample of the lunar soil and tucked the bag into a pocket on his suit.

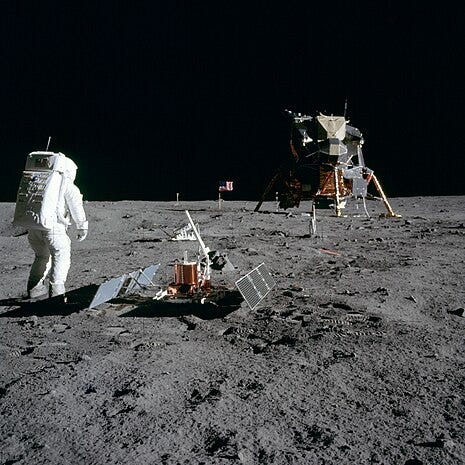

Aldrin then joined him on the surface, describing the view as “magnificent desolation.” The two experimented with moving around. Their backpacks, even in the one-sixth gee of the moon, tended to pull them backward, but they had no problem balancing. Aldrin attempted moving by hopping like a kangaroo, but they eventually determined that loping, taking long, bounding strides, was easiest.

One of their tasks was planting an American flag. It wasn’t easy, and they struggled with the telescoping rod and then could only drive it five inches into the hard surface. Because there was no atmosphere, the flag was designed to hang from the flagpole as if it was being flown by a stiff wind.

At that point, NASA patched in a telephone call from President Richard Nixon. Frank Borman, who was the NASA liaison to the White House had convinced the President to keep his remarks brief. Nixon concluded by saying, “For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one: one in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.”

Armstrong and Aldrin then deployed the experiment package they had brought with them. It included a passive seismic device and a reflector array to enable an Earth-based laser ranging experiment. They took photographs and collected samples. Aldrin attempted to take core samples, but again, the hard lunar surface made it impossible to penetrate more than six inches.

The moonwalk had gone well enough that Mission Control had granted a fifteen-minute extension. But after about two and a half hours on the surface, the expedition came to a close. They loaded the film they had taken and two containers of samples weighing 47.5 pounds into the Eagle. Then they tossed out their backpacks, overshoes and other unnecessary items to lighten the load. They sealed the hatch and repressurized the Eagle before settling down for a rest period that lasted about seven hours. After their adventure, neither man slept much.

Once they were officially up again, they began the countdown to liftoff. Two and a half hours later, they fired the Ascent engine and rose quickly to meet the Columbia in orbit. The exhaust from the engine knocked the flag over, something that NASA would correct on later flights by moving the flag farther from the Lunar Module.

A number of items left behind deliberately as memorials. A plaque on the descent stage bore the inscription: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.” They also left behind an Apollo 1 mission patch in memory of Grissom, White, and Chaffee.

While Armstrong and Aldrin had explored the surface, Michael Collins kept occupied with his duties aboard Columbia. He later reported that he hadn’t been lonely but had felt “awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation.” He was also ready, at any point, for an emergency rescue that he might need to make.

But the Eagle’s reunion with Columbia went according to plan. After docking, the crew transferred their samples and film to Columbia. After running through the checklist, the SPS fired and put them on a trajectory home.

An approaching storm forced NASA to shift the recovery zone in the Pacific. The recovery helicopters spotted Columbia when the drogue parachutes were released. After splashdown, the Columbia floated upside down for ten minutes until the floatation system righted the spacecraft. Navy divers added floatation collars and positioned rafts around Columbia.

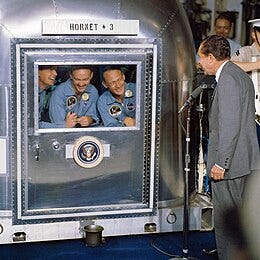

Concerned about the possibility the crew had been exposed to dangerous pathogens, NASA was taking extraordinary steps to ensure nothing would be spread. Before they left the spacecraft, divers handed the crew biological isolation suits to wear. When they finally made it into the rafts, both the astronauts and divers were scrubbed down with a bleach solution. They were then lifted into the recovery helicopter and flown to the U.S.S. Hornet. The helicopter was lowered to the hangar bay, and the astronauts walked thirty feet to the Mobile Quarantine Facility, a fancy name for a converted Airstream trailer. They would spend the next twenty-one days there to ensure they hadn’t been infected with anything. NASA would drop these precaution after the flight of Apollo 14 when it was clear the moon was sterile.

Columbia was lifted aboard and set in pace next to the quarantine trailer. A flexible tunnel between the two was installed, and the samples, film and other gear were transferred. When the Hornet arrived in Pearl Harbor, the trailer was airlifted to the Manned Space Center in Houston. The crew and their samples were transferred to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory. They were finally released on August 10th.

Three days later, the crew took part in ticker-tape parades in both New York and Chicago. They then flew to Los Angeles where the President hosted a state dinner. A month later, they addressed a joint session of Congress. They toured the world, visiting twenty-two countries in thirty-eight days. They were hailed as heroes everywhere they went.

The Space Race was over. NASA had met John F. Kennedy’s challenge. The Soviets, for their part, denied there had ever been a race to the moon. In 1989, that charade was revealed.

Regardless, Apollo wasn’t done. There was much left to discover and explore.

I had to watch from pine scrub behind the Title Co. office i worked at in Melbourne, recording Warranty Deeds, Mortgages in a log, all summer, on my vacation from UF, no fun. I was a rising Junior. They wouldn't let me off to see the launch... reading this gave me goosebumps, thanks Michael, for sharing, lb Was down in Hollywood visiting my gal from school, we watched Armstrong exit with her parents. we all remember where we were